Hugging Face Transformer Inference Under 1 Millisecond Latency

Go to production with Microsoft and Nvidia open source tooling

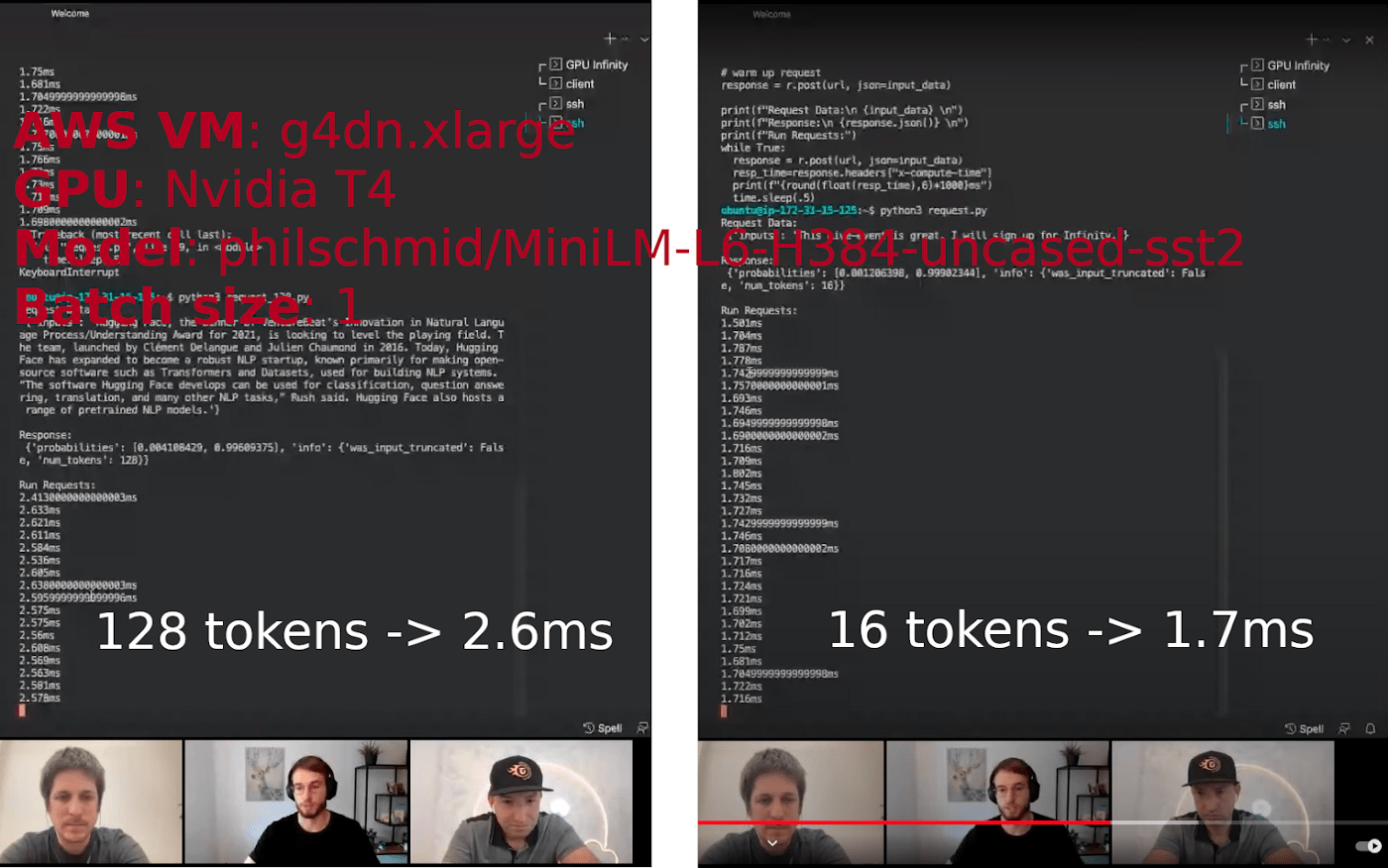

Recently, 🤗 Hugging Face (the startup behind the transformers library) released a new product called “Infinity’’. It’s described as a server to perform inference at “enterprise scale”. A public demo is available on YouTube (find below screenshots with timings and configuration used during the demo). The communication is around the promise that the product can perform Transformer inference at 1 millisecond latency on the GPU. According to the demo presenter, Hugging Face Infinity server costs at least 💰20 000$/year for a single model deployed on a single machine (no information is publicly available on price scalability).

It made me curious to dig a bit and check if it was possible to reach those performances with the same AWS VM/model/input that used in the demo (see screenshot below for details), using open source tooling from Microsoft and Nvidia? Spoiler: yes it is and with this tutorial, it’s easy to reproduce and adapt to your REAL LIFE projects.

💻 The project source code is available at this address:

https://github.com/ELS-RD/transformer-deploy

The README provides instructions on how to run the code and has been tested both on an AWS VM with deep learning image version 44 and a bare metal server with a Nvidia 3090 GPU (measures published in the article are from the AWS machine).

If you are interested in this topic, follow me on Twitter: https://twitter.com/pommedeterre33

I work at Lefebvre Sarrut R&D, a leading European legal publisher, and my team has deployed quite a bunch of models in production, including several transformers, from small distilled models to large ones, to perform a variety of tasks on legal documents. Some of these works have been described here and there.

In this article we will see how to deploy a modern NLP model in an industrial setup. Dozens of tutorials exist on the subject, but, as far as I know, they are not targeting production, and don’t cover performance, scalability , decoupling CPU and GPU tasks or GPU monitoring. Some of them look like: 1/ take FastAPI HTTP server, 2/ add Pytorch, and voilà 🤪

If you have interesting content you want me to link to, please post in comments…

The purpose of this tutorial is to explain how to heavily optimize a Transformer from Hugging Face and deploy it on a production-ready inference server, end to end. You can find some interesting and technical content from Nvidia and Microsoft about some specific parts of this process.

The closest match and an inspiration for me is this article. It still misses 2 critical points, significant optimization and tokenization on inference server side (otherwise you can’t easily call the inference server outside of Python). We will cover those 2 points.

The performance improvement brought by this process applies to all scenarios, from short sequences to long ones, from a batch of size 1 to large batches. When the architecture is compliant with the expectations of the tools, the process always brings a significant performance boost compared to vanilla PyTorch.

The process is in 3 steps:

- Convert Pytorch model to a graph

- Optimize the graph

- Deploy the graph on a performant inference server

At the end we will compare the performance of our inference server to the numbers shown by Hugging Face during the demo and will see that we are faster for both 16 and 128 tokens input sequences with batch size 1 (as far as I know, Hugging Face has not publicly shared information on other scenarios).

More importantly, more machine learning practitioners will be able to do something far more reliable than deploying an out of the box Pytorch model on non-inference dedicated HTTP server.

From Pytorch to ONNX graph

You probably know it, the big selling point of Pytorch compared to Tensorflow 1.X has been its ease of use: instead of building a graph you just write familiar imperative code. It feels like you are writing numpy code running at GPU speed.

Making users happy is awesome, what is even more awesome is to also make optimization tools happy. Unlike humans, those tools love graphs to perform (sometimes offline) analysis. It makes sense, graphs provide a static and complete view of the whole process, from data point to model output. Moreover, the graph provides an intermediate representation which may be common to several machine learning frameworks.

We need a way to convert our imperative Pytorch code to a graph. Several options exist, but the one we are interested in is called ONNX. “ONNX is an open format built to represent machine learning models. ONNX defines a common set of operators — the building blocks of machine learning and deep learning models — and a common file format to enable AI developers to use models with a variety of frameworks, tools, runtimes, and compilers.” (https://onnx.ai/). The format has initially been created by Facebook and Microsoft to have a bridge between Pytorch (research) and Caffee2 (production).

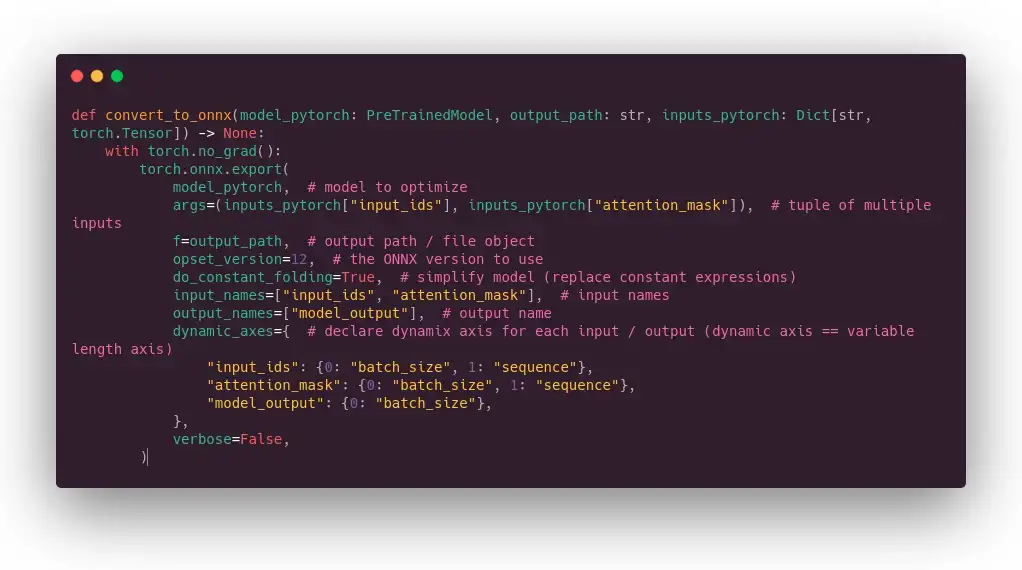

Pytorch includes an export to ONNX tool. The principle behind the export tool is quite simple, we will use the “tracing” mode: we send some (dummy) data to the model, and the tool will trace them inside the model, that way it will guess what the graph looks like.

Tracing mode is not magic, for instance it can’t see operations you are doing in numpy (if any), the graph will be static, some if/else code is fixed forever, for loop will be unrolled, etc. It’s not a big deal because Hugging Face and model authors took care that main/most models are tracing mode compatible.

For your information, there is another export mode called “scripting” which requires the models to be written in a certain way to work, its main advantage is that the dynamic logic is kept intact but it would have added too many constraints in the way models are written for no obvious performance gain.

Following commented code performs the ONNX conversion:

One particular point is that we declare some axis as dynamic. If we were not doing that, the graph would only accept tensors with the exact same shape that the ones we are using to build it (the dummy data), so sequence length or batch size would be fixed. The name we have given to input and output fields will be reused in other tools.

Please, note that ONNX export also works for feature extraction like done in sentence-transformers library but in that case it requires some little tricks.

🥳 Félicitations, you know how to have a graph ready to be optimized!

Graph optimization: 2 tools, 1 mission

We will focus on 2 tools to optimize Pytorch models: ONNX Runtime from Microsoft (open source under MIT license) and TensorRT from Nvidia (open source under Apache 2 license, the optimization engine is closed source).

They can work alone or together. In our case, we will use them together, meaning using TensorRT through ONNX Runtime API.

> #protip: if you want to sound like a MLOps, don’t say ONNX Runtime / TensorRT, but ORT and TRT. Plus you may find those names in Github issues/PR.

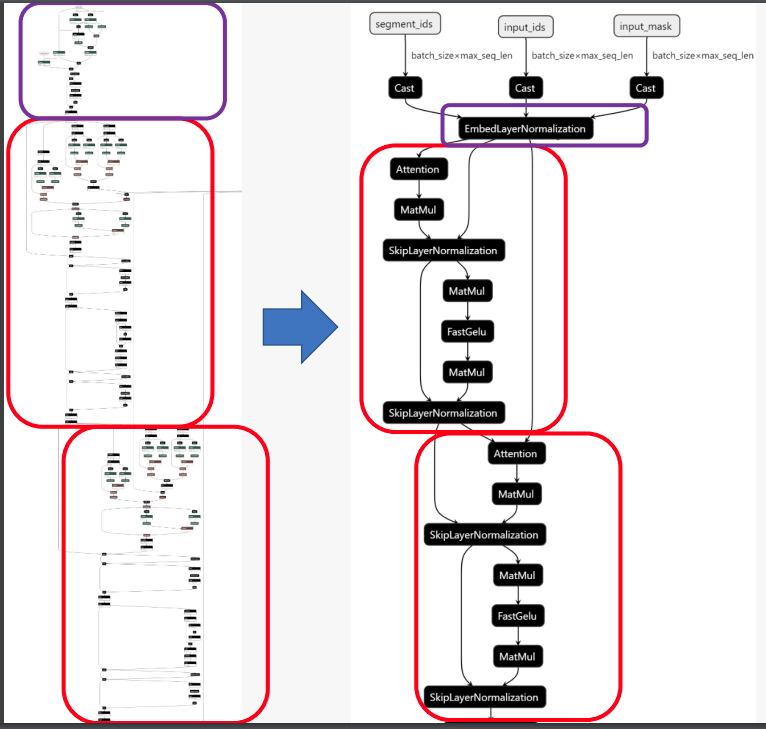

Both tools perform the same kind of operations to optimize ONNX model:

- find and remove operations that are redundant: for instance dropout has no use outside the training loop, it can be removed without any impact on inference;

- perform constant folding: meaning find some parts of the graph made of constant expressions, and compute the results at compile time instead of runtime (similar to most programming language compiler);

- merge some operations together: to avoid 1/ loading time, and 2/ share memory to avoid back and forth transfers with the global memory. Obviously, it will mainly benefit to memory bound operations (like multiply and add operations, a very common pattern in deep learning), it’s called “kernel fusion”;

They can optionally convert model weights to lighter representations once for all (from 32-bit float to 16-bit float or even 8-bit integers in case of quantization).

Netron can produce display of ONNX graph before and after optimization:

Both tools have some fundamental differences, the main ones are:

- Ease of use: TensorRT has been built for advanced users, implementation details are not hidden by its API which is mainly C++ oriented (including the Python wrapper which works exactly the way the C++ API does, it may be surprising if you are not a C++ dev). On the other hand, ONNX Runtime documentation is easy to understand even if you are not a machine learning hardware expert, offers a Pythonic API plus many examples in this language, and you will find more NLP dedicated examples and tools.

- Scope of optimizations: TensorRT usually provides the best performance. The process is slightly tricky, I won’t provide details here, but basically you build “profiles” for different associations of hardware, model and data shapes. TensorRT will perform some benchmark on your hardware to find the best combination of optimizations (a model is therefore linked to a specific hardware). Sometimes it’s a bit too aggressive, in particular in mixed precision, the accuracy of your transformer model may drop. To finish, let’s add that the process is non-deterministic because it depends on kernel execution time. To make it short, we can say that the added performance brought by TensorRT has a learning curve cost. ONNX Runtime has 2 kinds of optimizations, those called “on-line” which are automagically applied just after the model loading (just need to use a flag), and the “offline” ones which are specific to some models, in particular to transformer based models. We will use them in this article. Depending on the model, the data and the hardware, ONNX Runtime + offline optimizations are sometimes on par with TensorRT, other times I have seen TensorRT up to 33% faster on real scenarios. TensorRT API is more complete than what is exposed through ONNX Runtime, for instance you can tell which tensor shape is optimal, and fix some limits on dimensions, therefore it will generate all required profiles. If you really need best performances, you need to learn TensorRT API.

- Multiple backends: ONNX Runtime has its own CUDA and CPU inference engines, but it can also delegate the inference to third party backends… including TensorRT, TVM or openVINO! In those cases, ONNX Runtime is a nice and well-documented API to leverage a more complex tool. You know what? We will test that below!

- Multiple hardware targets: TensorRT is dedicated to Nvidia hardware (many GPUs and Jetson), ONNX Runtime targets GPU (Nvidia CUDA and AMD RocM), CPU, edge computing including browser deployment, etc.

In case you didn’t get it, ONNX Runtime is your good enough API for most inference jobs.

Regarding the transformer architectures supported, you can have a basic idea of what ONNX Runtime is capable of by checking this page. It includes Bert, Roberta, GPT-2, XLM, layoutlm, Bart, T5, etc. Regarding TensorRT, I have tried many architectures without any issue, but as far as I know, there is no list of tested models. At least you can find T5 and GPT-2 notebooks there, with up to X5 faster inference compared to vanilla Pytorch.

According to this README, Nvidia is working hard to ease transformers acceleration on its framework and this is great news for all of us!

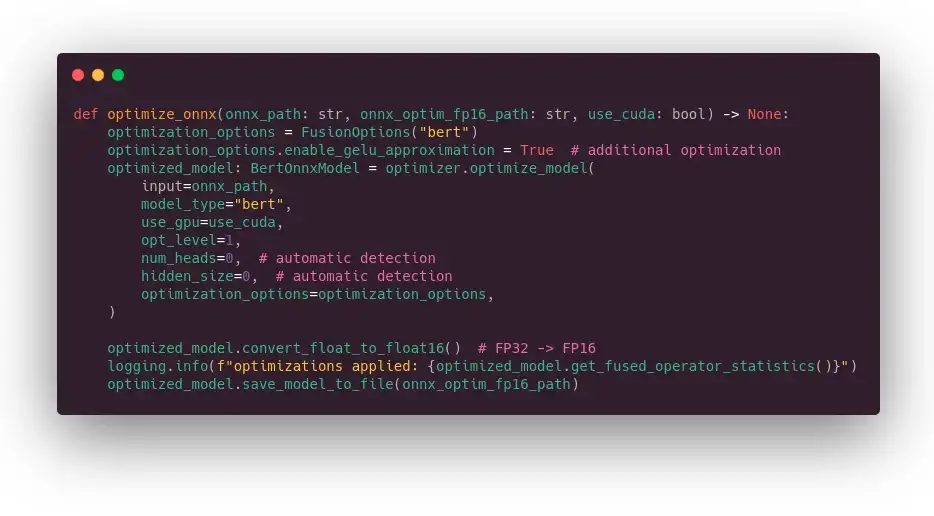

Offline optimizations

As said previously, some optimizations are applied just after loading the model in memory. There is also the possibility to apply some deeper optimizations while performing a static analysis of the graph, so that it will be easier to manage the dynamics axis or drop some unnecessary casting nodes. Moreover, changing model precision (from FP32 to FP16) requires being offline. Check this guide to learn more about those optimizations.

ONNX Runtime offers such things in its tools folder. Most classical transformer architectures are supported, and it includes miniLM. You can run the optimizations through the command line:

In our case, we will perform them in Python code to have a single command to execute. In the code below, we enable all possible optimizations plus perform a conversion to float 16 precision.

A part of the performance improvement comes from some approximations performed at the CUDA level: on the activation layer (GELU) and on the attention mask layer. Those approximations can have a small impact on the model outputs. In my experience, it has less effect on the model accuracy than using a different seed during training.

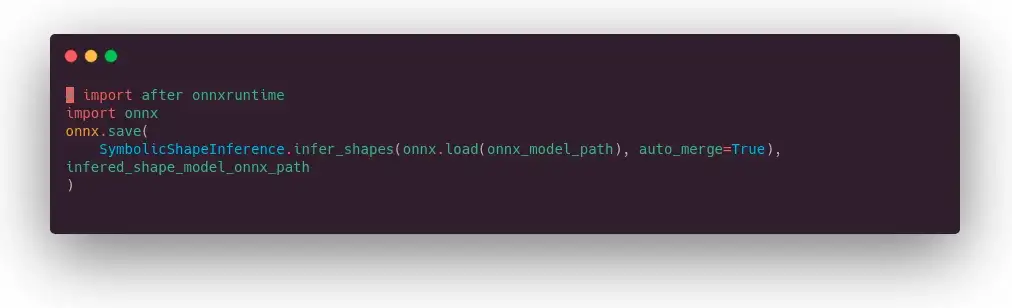

Regarding TensorRT, there are no offline optimizations but it’s advised in ONNX Runtime documentation to perform symbolic shape inference on the vanilla ONNX model. This is useful because it may happen that ONNX Runtime splits the graph in several subgraphs, and because of that the (tensor) shape information is lost for TensorRT. Symbolic shape inference will put back the information everywhere it’s required. And if like me, you are wondering why it’s called symbolic, it’s because it will really perform symbolic computation with a Python lib called sympy dedicated to… symbolic computation in general.

A word about GPU int-8 quantization

CPU quantization works out of the box, GPU is another story. You may have seen benchmarks from Nvidia showing amazing performances with int-8 quantization compared to FP16 precision and may wonder, why you can’t find any NLP tutorial to do the same (in CV there is quite a bit).

There are several reasons why :

- First, transformers quantization has been fully enabled since TensorRT 8, which was released last summer.

- Second, the existing tooling (the one I tried at least) is buggy, the documentation is not always up to date, and it doesn’t work well with the last version of Pytorch (I experienced an issue to export graph including QDQ nodes). Still, if you dig a bit in Pytorch code, you can work around the bug with a dirty patch.

- Third, the results are hardware dependent, meaning lots of experimentations for different shapes/models/hardware associations.

- Fourth, depending on your quantization approach, it can make your model slower than in FP16 by adding plenty of “reformatting” nodes.

Quantization brings its best performance with large flavors of transformer architectures because, beyond the reduction of calculations, it reduces memory transfers of its many weights in a way that no kernel fusion can reach.

Another thing to keep in mind is that not all models can be int-8 quantized out of the box, sometimes you will get some “Could not find any implementation for node …” error message meaning you are good to rework the model, wait for a new version of TensorRT, or, if you have lots of free time, fork TensorRT like here. Vanilla Bert works well. miniLM works on some tools, but not all, not sure why.

Not all layers should be quantized. Post training quantization quantizes all layers and is performance focused (but accuracy may drop), it’s up to the user to choose the layers he wants to exclude to keep high accuracy. Query aware training only quantize specific layers, in Bert case you will find attention layers for instance, therefore it’s usually a trade-off between accuracy and performance.

To finish, calibration (a required operation to convert floats to integers and a scale) is still an unsolved problem, there are several options and you need again to experiment to find the ones which works for your model and your task.

For more information on quantization, you can check this very good paper from Nvidia: https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.09602

When you are working at internet scale like Microsoft, it makes sense to invest in this technology. For most of us, it’s not obvious until the software part is improved.

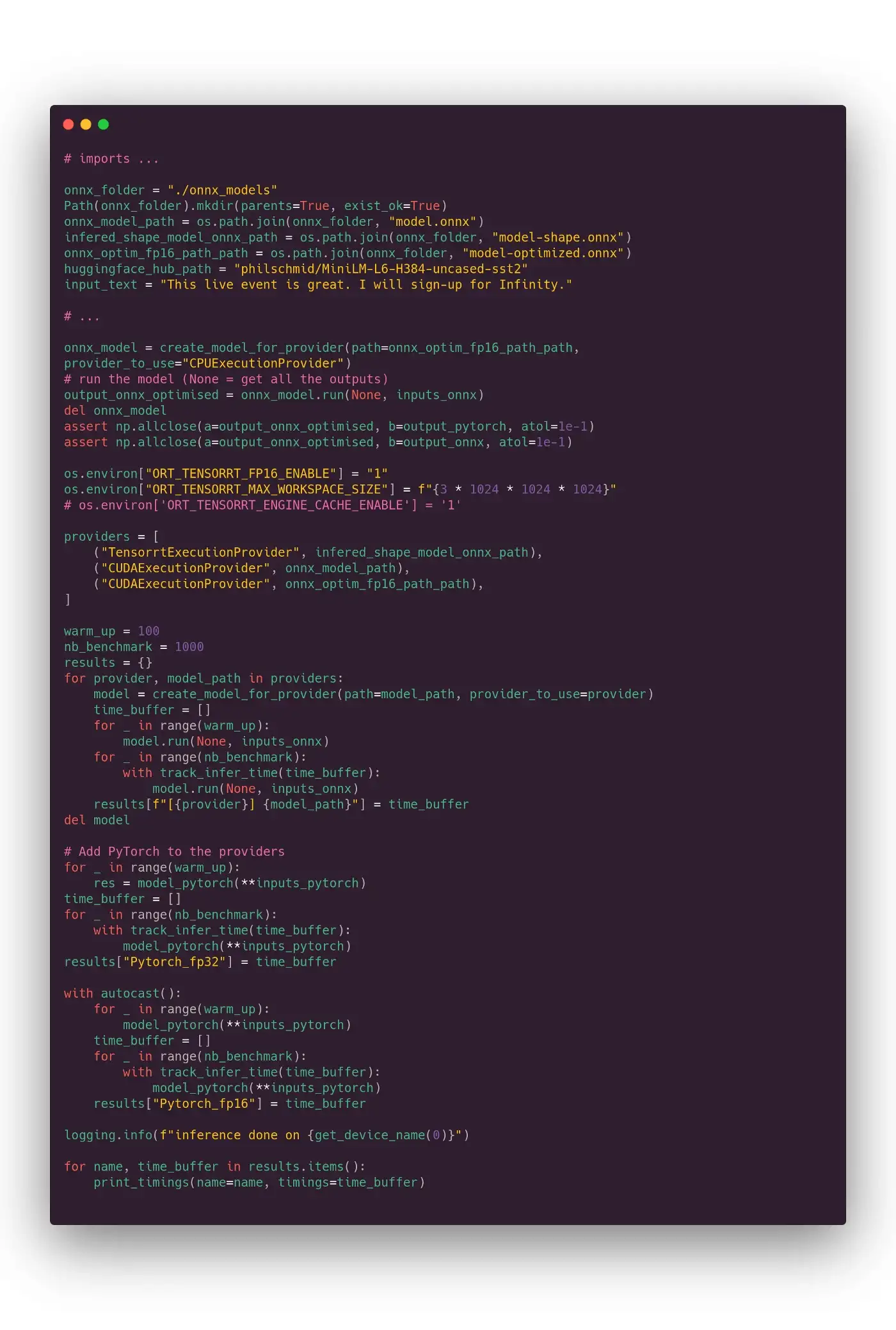

⌛Inference benchmarks (local execution)

Ok, now it’s time to benchmark. For that purpose we will use a simple decorator function to store each timing. The rest of the code is quite straightforward. Measures at the end of the script are performed with 16 tokens input (like one of the measures in the Infinity demo).

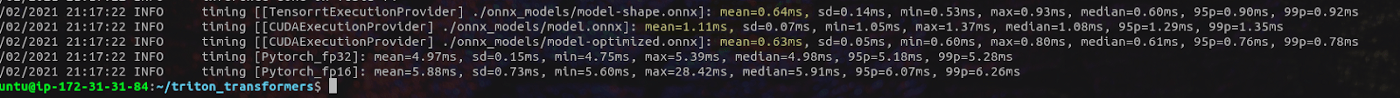

Results below:

💨 0.64 ms for TensorRT (1st line) and 0.63 ms for optimized ONNX Runtime (3rd line), it’s close to 10 times faster than vanilla Pytorch! We are far under the 1 ms limits.

We are saved, the title of this article is honored :-)

It’s interesting to notice that on Pytorch, 16-bit precision (5.9 ms) is slower than full precision (5 ms). This is due to our input, there is no batching, the sequence is very short, and at the end of the day, the casting from FP32 to FP16 adds more overhead than the computation simplification it implies.

Of course we have checked that all model outputs are similar (they won’t be equal because of small approximation, as explained above, plus different backend performs rounding inside the graph slightly differently).

Outside of benchmarks or corner case use cases, it’s not every day that you perform inference on a single 16 sequence tokens on a very small model on a GPU because it doesn’t take advantage of GPU main strength. Moreover, even if your queries come as single sequence, most serious inference servers have a feature to combine individual inference requests together in batches. The purpose is to exchange few milliseconds of latency against an increased throughput, which may be what you are looking for when you try to optimize your hardware total cost of ownership.

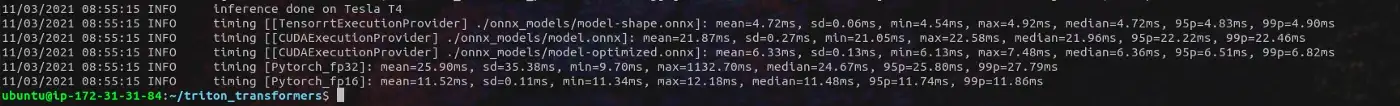

Just for your information and not related to the Hugging Face demo, please find below measures on the same virtual

machine (T4 GPU) for bert-base-uncased, sequence of 384 tokens and batch of size 32 (those are common parameters we

are

using in our use cases at Lefebvre Sarrut):

As you can see, the latency decrease brought by TensorRT and ONNX Runtime are quite significant, ONNX Runtime+TensorRT latency (4.72 ms) is more than 5 times lower than vanilla Pytorch FP32 (25.9 ms) ⚡️🏃🏻💨💨 ! With TensorRT, at percentile 99, we are still under the 5 ms threshold. As expected, here FP16 on Pytorch is approximately 2 times faster than FP32 as and ONNX Runtime alone (CUDA provider) performs a good job quite similar to TensorRT provider.

These results should not surprise us as it seems we are using the same tooling than Hugging Face.

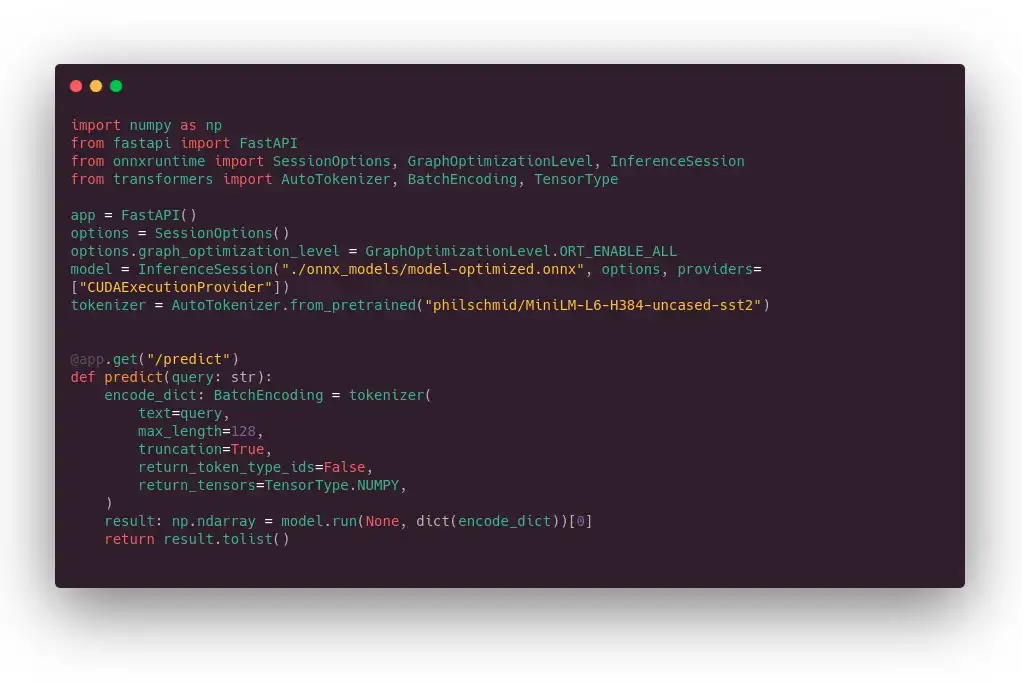

🍎 vs 🍎: 1st try, ORT+FastAPI vs Hugging Face Infinity

It wouldn’t be fair to compare the timings from the precedent section with those from the Hugging Face demo: we have no server communication, no tokenization, no overhead at all, we just perform the inference.

So, we will do it again, but this time with a simple HTTP server: FastAPI (like in the dozens of marketing content you can find on AI startup blogs).

Please note that, whatever its performance, FastAPI is not a good inference server choice to go on production, it misses basic things like GPU monitoring, advanced ML performance tooling, etc.

The timing looks like that:

[sarcasm on] Whhhhhhhaaaaaat???? Performing the inference inside fastAPI is 10 times slower than local inference? What a surprise, who would have expected that? [sarcasm off]

If we check on a well-known web framework benchmark, we can see that FastAPI is not that fast compared to other options from other languages. It’s even among the slowest on the single query latency side (over 38X slower than fasthttp Go server). It doesn’t make it a bad software, of course, it’s really a nice tool to use with its automatic typing, etc., but it’s not what we need here.

Hugging Face has only communicated on very short (16) and short (128) sequences with batch size of 1. The model is optimizable with off-the-shelf tooling, but the end to end performance is not reachable if we stay in the Python world. In some other scenario (large batch, long sequence), few milliseconds overhead difference may have been insignificant.

So, what do we use if not fastAPI?

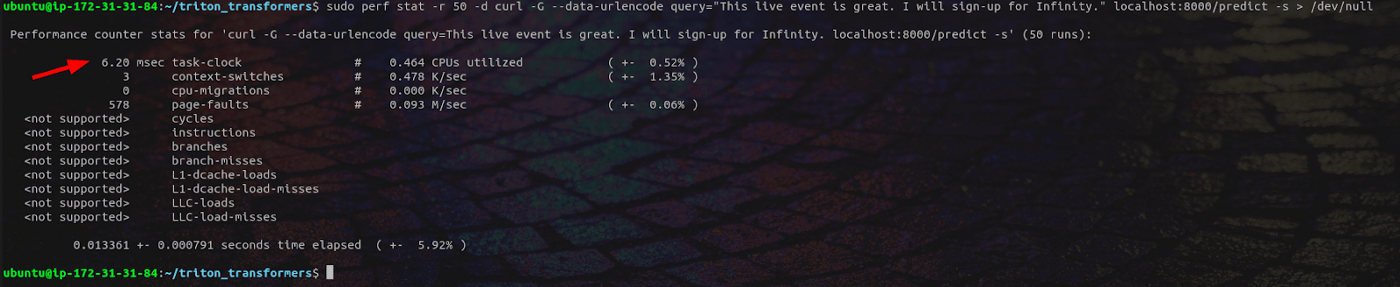

🍎 vs 🍎: 2nd try, Nvidia Triton vs Hugging Face Infinity

Nvidia has released a beautiful inference server called Triton (formerly known as TensorRT which was very confusing).

It offers close to everything you may need, GPU monitoring, nice documentation, the best error messages I have ever seen (seriously, it’s like they put someone inside to tell you what to fix and how). It has plenty of very powerful possibilities (that we won’t detail in this already too long tutorial) and is still easy to use for simple cases. It provides a GRPC plus a HTTP API, quite a performant client for Python (requests library is like FastAPI, simple API, close to perfect documentation, but so-so performances) and a good C++ one. It comes with a bunch of serious tools to optimize hardware usage. To better understand what makes a good inference engine, check https://arxiv.org/pdf/2011.02327.pdf

For reasons I don’t get, it’s not a very well-known tool in the NLP community (the situation is a bit better in the CV community).

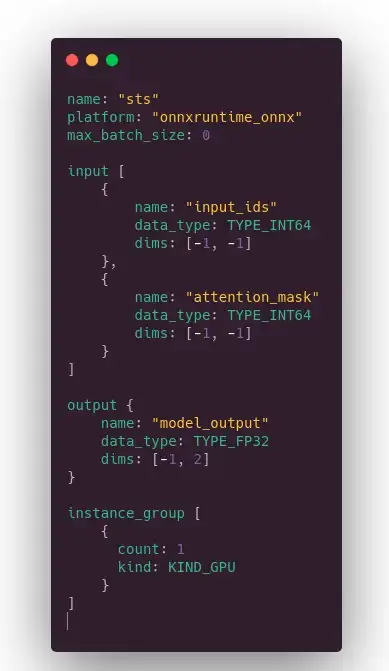

1/ Setting up the ONNX Runtime backend on Triton inference server

Inferring on Triton is simple. Basically, you need to prepare a folder with the ONNX file we have generated and a config file like below giving a description of input and output tensors. Then you launch the Triton Docker container… and that’s it!

Here the configuration file:

2 comments:

- max_batch_size: 0 means no dynamic batching (the advanced feature to exchange latency with throughput described above).

- -1 in shape means dynamic axis, aka this dimension may change from one query to another

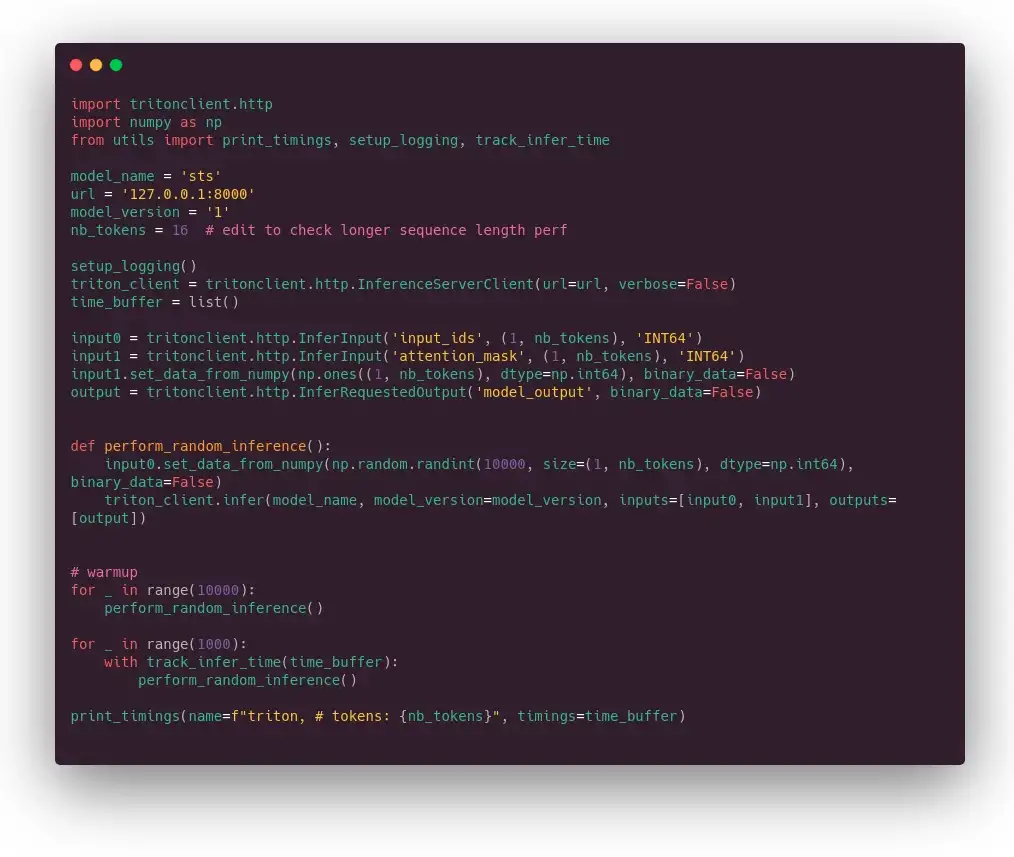

2/ Setting up the client

In the repo associated with this article (link at the beginning), there are 2 Python client scripts, one based on the tritonclient library (performant), one based on requests library (not performant but useful as a draft if you need to call Triton outside Python) and a simple curl call (in the repository README).

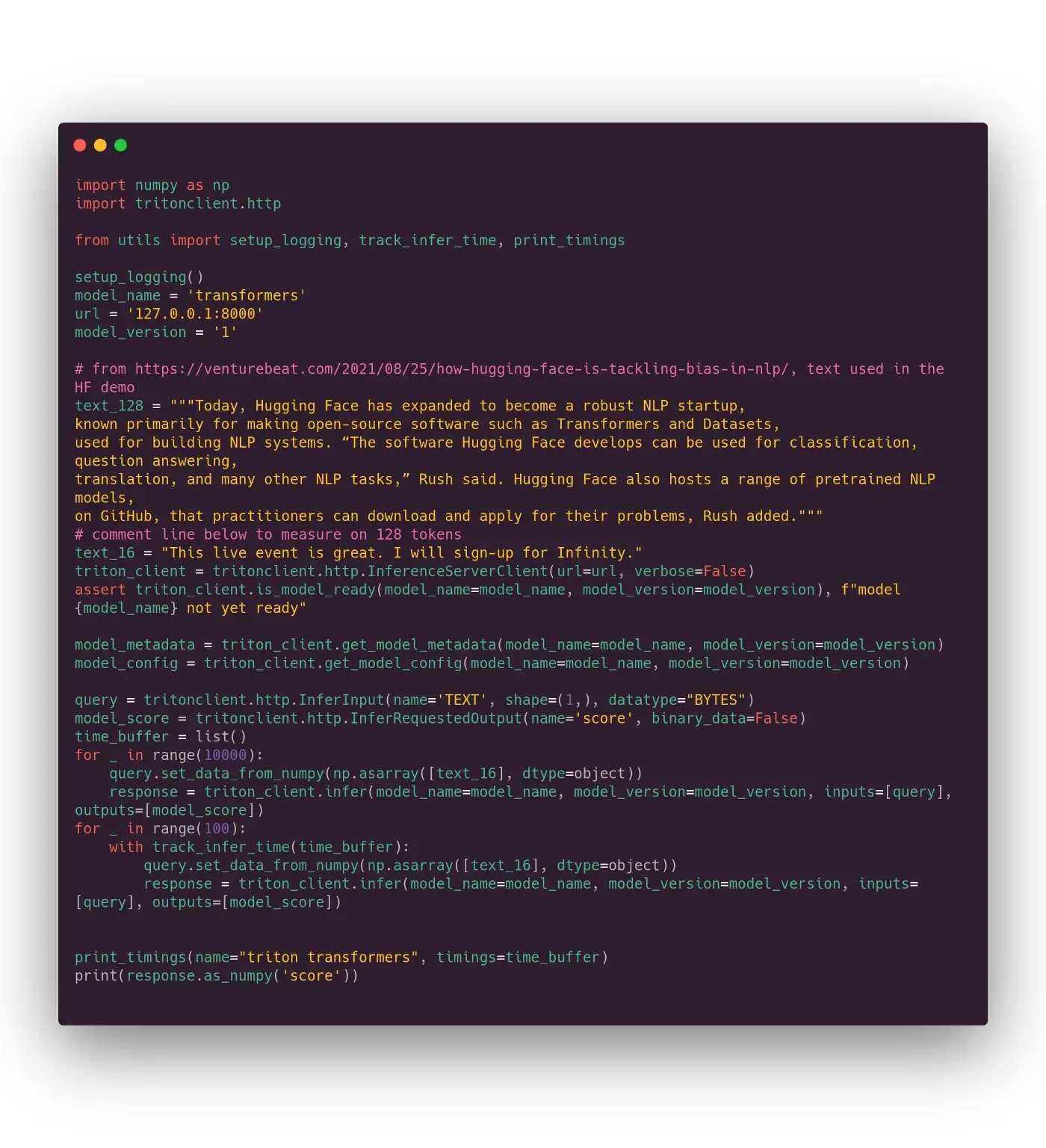

Our tritonclient based script to query Triton inference server:

The little subtlety in the client library is that you first declare the input and output variables and then load data into them.

Note that input ids tensor is randomly generated for each request, to avoid any cache effect (as far as I know, there is no cache by default but always good to check).

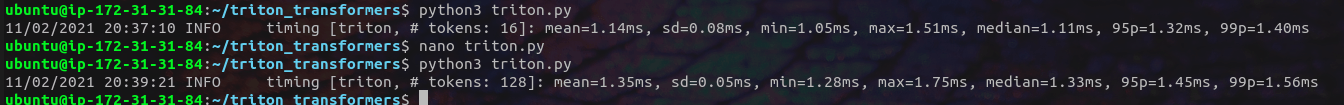

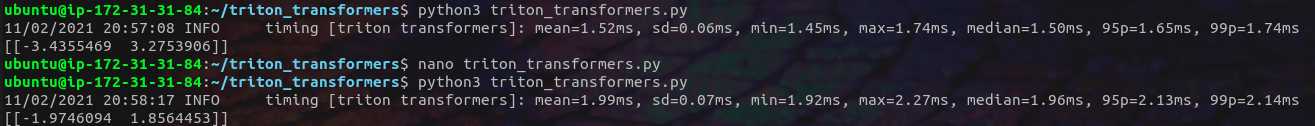

Results for 16 (first measure) and 128 token (second measure) input length:

Awesome, we are onto something: for both 16 and 128 tokens sequence length we are under still the Hugging Face baseline. The margin is quite significant in 128 token case.

We are still doing pure model computations on the GPU, to have something we can compare to Hugging Face Infinity we still need to move the tokenization part to the server.

3/ Adding the tokenization on the server side

Did I tell you that the Nvidia Triton server is awesome? It is. It supports several backends including one called “Python”. In the Python backend we can call free Python code, for instance to prepare our data (tokenization in our case).

Before implementing this part, you need to install transformers in the Triton Docker container. Check the README of the repository associated to this article for more information.

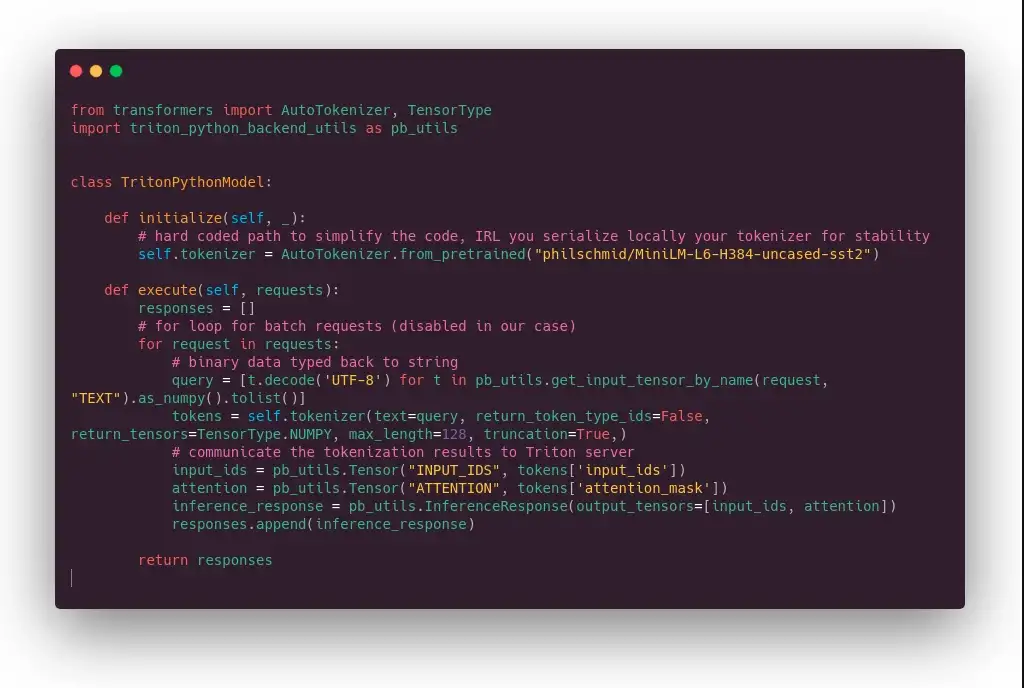

What the Python code looks like:

Basically, there is a kind of __init__() function where we download the tokenizer, and an execute function to

perform the

tokenization itself. The for loop is because of the dynamic batching function. Very short and simple code.

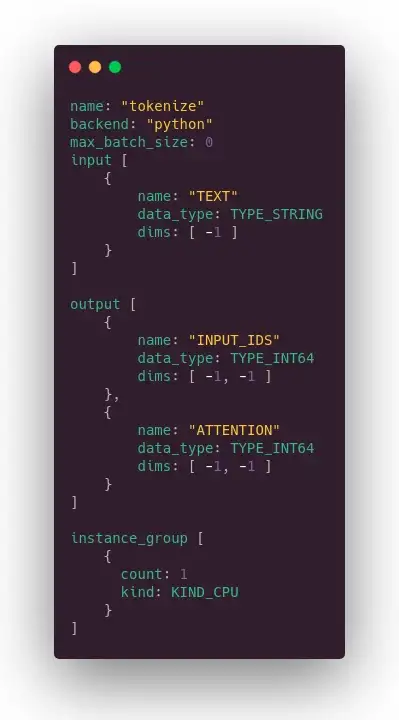

We need a configuration to tell Triton what to expect as input and output.

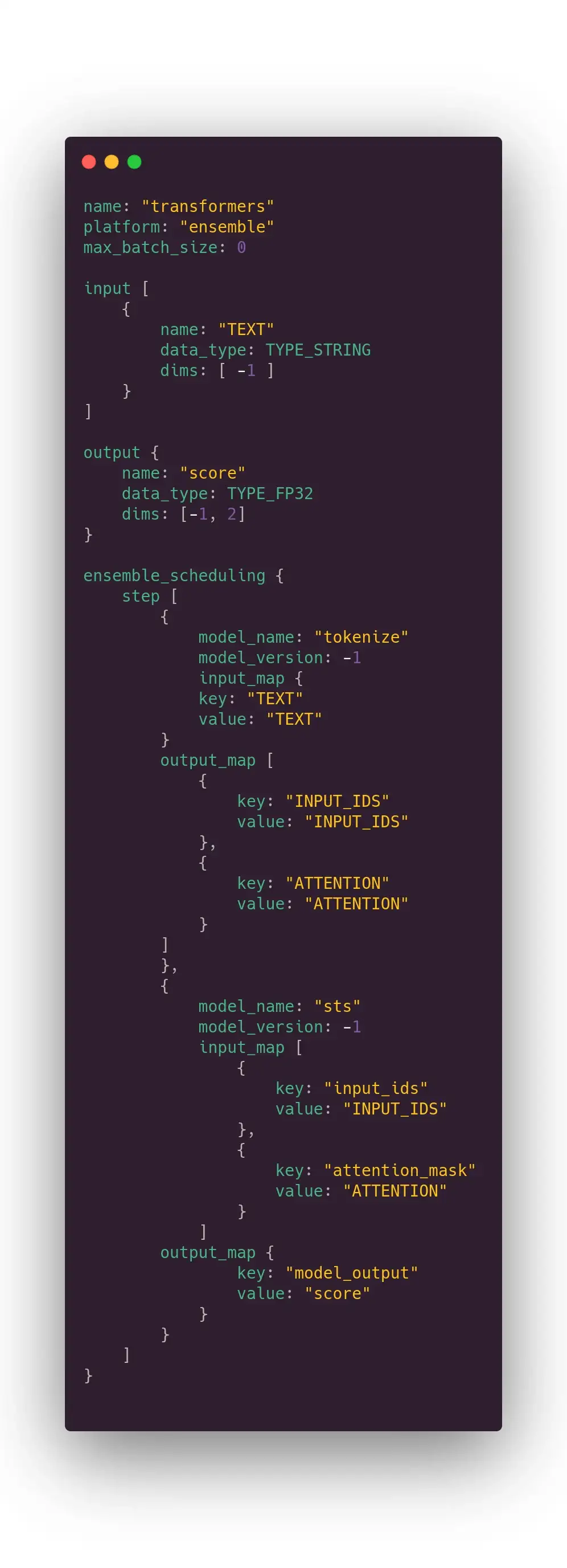

Now we want to plug the tokenizer to the model, we need a 3rd configuration.

First part declare the input and the output of the whole process, the second one plug everything together. Basically, it says receive a string, send it to the tokenizer, get the output from the tokenizer and pass it as input of the model, return the model output.

As said before, the server documentation is well written. It’s easy to use the wrong type, the wrong dimension, or insert a typo in tensor name, Triton error messages will tell you exactly what to fix and where.

4/ 👀 final benchmarks!

Finally, here is the time of the final benchmark. Below you can see our final client script. The main difference with the previous client script is that we are now targeting the full process and not just the model. We don’t send integer tensors but just the string (stored in a numpy array which is the way to communicate with Triton).

And the measures for 16 (first measure) and 128 (second measure) tokens:

🎯 We made it! 1.5ms for 16 tokens (vs 1.7 ms on Hugging Face Infinity) and 2ms for 128 tokens length (vs 2.5 ms on Hugging Face Infinity).

We have built a fast inference server ready to be deployed in our clusters. We will now enjoy how GPU monitoring makes auto scaling easier to set up, or how mature performance measure tooling will help us to fix bottlenecks in our pipelines. And this is absolutely awesome for machine learning practitioners, startups and enterprises.

So now, what can we expect from the future?

Outro

Unlike what you will read in some media, many think that the machine learning community is still in its infancy. In particular, there is a topic coming again and again that most of the machine-learning projects have never been deployed in production, it would be just marketing content and posts from machine learning enthusiasts, like in Why 90 percent of all machine learning models never make it into production or Why do 87% of data science projects never make it into production? or Why ML Models Rarely Reaches Production and What You Can Do About it, etc.

Obviously, someone used GPT-9 to generate these contents. If you know where to download the weights of GPT-9, please drop me a PM :-)

I doubt anyone can really measure it, but for sure there are too few serious articles on NLP model deployment. I hope you enjoyed that one and my hope is that, if you have the time for it, maybe you can share your optimization/deployment experience with the community on Medium or elsewhere. There are so many other important things to fix in NLP, CPU/GPU deployment should not be a challenge in 2021.

As a community, we also need appropriate communication from key players, even when it comes to selling products to enterprises. For instance, messages like “it takes 2 months x 3 highly-skilled ML engineers to deploy and accelerate BERT models under 20ms latency” miss key technical details (model, input size, hardware), making any comparison impossible. Moreover, calling these engineers “highly skilled” and still unable to achieve their goal after months of work implies fear, uncertainty and doubt about our own ability to do the same.

And to finish, we need more inference optimizations targeting NLP models in open source tools!

At the bi-LSTM/GRU & friends time, and during a few years, it was like there was a big architecture change every month. Then transformer came, and ate most NLP tasks. There were still some architecture variations, and the Hugging Face Transformers library was here to help machine learning practitioners to follow the hype without big investment in code rewriting.

I have the feeling that model architectures have now stabilized and that the fear of missing the latest trendy architecture is decreasing in the community.

To say it differently, if you already have in your toolbox a Roberta, a distilled model like miniLM, and a generative model like T5 or Bart, you are probably ok for most industrial NLP use cases for 1 or 2 years.

It’s good news for machine learning practitioners, because this stabilization opens the door to increased efforts from Microsoft, Intel, Nvidia and others to optimize NLP models. Big latency time reduction or highly increased throughput will not only be translated into lower-cost inference, but also by new usage and new products. We may also hope that someday, we can even use those very large language models (those in the hundreds of billions of parameters) that are supposedly able to do plenty of awesome things. I am personally confident that it will happen as it’s in the interest of hardware builders and cloud providers to develop NLP usages, and they have both resources and the knowledge to do these things.