Deep Dive into Kernel Fusion: Accelerating Inference in Llama V2

The code is available at https://github.com/ELS-RD/kernl/tree/main/experimental/llama-v2.

Llama, the most widely discussed machine learning model in 2023, has recently received an upgrade with the release of Llama V2. Its new licensing terms have sparked significant excitement in the field, reaffirming its position at the forefront of the local model run movement. This movement emphasizes low-level optimizations, with a particular focus on platforms like MacBook Pro, evidenced by the llama.cpp project and numerous published quantization schemes. Like its contemporaries, Llama V2's design rests on the Transformer architecture. However, its distinct attributes include the use of Rotary Positional Embeddings (RoPE) over conventional positional encoding, RMSNorm replacing LayerNorm, and the integration of the SILU function in the feed-forward components.

When we came across a tweet by Nat Friedman showing that llama.cpp could run the 7b parameters llama v1 model at a speed of 40 tokens per second, our curiosity was instantly piqued. This impressive speed does, however, rely on aggressive 4-bit quantization and recent high-end hardware, pricier than a (now) "old" 3090 RTX (released in Q4 2020). Yet, considering Nvidia GPUs were specifically designed for such tasks and MacBook M2 has a wider range of capabilities, it was a fair enough comparison.

In an effort to juxtapose the proverbial apples and pears, we tested the speed in terms of the number of tokens processed per second on a 3090 RTX GPU, using the FP16 model with 7B parameters. Astonishingly, it fell short of expectations, achieving a speed of only 23 tokens per second on average (llama v1), for a sequence length of 500, almost 2 times slower than llama.cpp on Apple hardware. It's important to note a few caveats with this comparison outside of the data type: the computation of the first token in a sequence is more intensive than the subsequent ones due to the KV cache, and Nvidia GPUs excel in this initial computation. Furthermore, it's not common to generate 500 consecutive tokens as the sequence may become unstable.

The following content has been revised to include numbers relevant to llama V2.

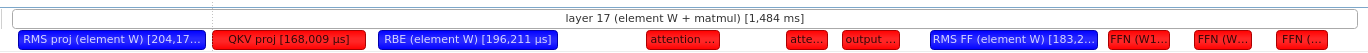

Our first action was to profile the model with Nvidia Nsight, specifically focusing on the generation of a single token (and batch=1). To our surprise, the results were unexpected:

In our investigation, we noticed that two specific transformations - the Rotary Positional Embeddings (RoPE) and RMSNorm - were taking up an unusually high amount of processing time. This came as a surprise because these operations are considered element-wise, meaning they perform calculations for each dimension individually, in contrast to more complex operations like matrix multiplication, which is a contraction operation (we consider interactions between different elements) and typically more resource-intensive.Furthermore, it is generally acknowledged that element-wise operations execute very quickly.

After some investigation, we traced the root of this issue back to the way these operations are implemented in PyTorch.

Each computation stage of those transformations necessitates invoking a separate PyTorch operator, each requiring its output to be saved to GPU global memory and the next operator requiring reloading the same data. On top of that, you have plenty of CPU overhead to execute Python code, to go through PyTorch internals, to call CUDA kernels, to launch CUDA kernels and setup execution scheduler, etc. Because we are in inference and a small batch size, there are not that many computations to do to hide this overhead. Consequently, this method becomes a hindrance in a GPU setting where data transfer (especially memory-related operations) can be more time-consuming than the computations themselves.

As we'll demonstrate, a tactful increase in the computational aspect can significantly decrease overall latency, effectively dealing with this bottleneck.

At the end we almost doubled the number of tokens generated per second: from 23 to 44. As said below, we just focused on some parts of the model, and let some optimization opportunities untapped.

Rotary Embeddings and Optimization: A Dive Into Complex Numbers

Our first step towards optimizing the Llama model's performance centers on transforming its rotary embeddings. The goal is to transition from the original implementation that heavily relies on complex numbers to a version that doesn't use these mathematical tools.

Before embarking on this journey, it's crucial to understand the role and nature of complex numbers in our context. Fundamentally, a complex number contains a real part and an imaginary part, typically represented as (a + bi). Here, 'a' is the real part, 'bi' is the imaginary part, 'b' is a real number, and 'i' represents the square root of -1. This structure enables complex numbers to be visualized on a two-dimensional plane, where the real part is on the x-axis and the imaginary part on the y-axis.

Within the realm of transformer models, Rotary Positional Embeddings, or 'RoPE', provide an original approach to encoding positional information of tokens in a sequence. Leveraging the nature of complex numbers, each token's position can be mapped as a point on a 2D plane. This mapping allows the application of a rotation to each token's embedding, with the intensity of the rotation linked to the token's sequence position.

But why complex numbers? Their structure naturally lends itself to efficient representation and manipulation of 2D rotations. Consequently, the rotation operation, a crucial element of rotary embeddings, can be executed efficiently. This technique becomes a powerful way to encapsulate the order of the sequence, thus fostering understanding of positional relationships between tokens.

Original Llama Implementation

The original Llama implementation uses complex number functions like polar and precomputes 'freqs' in the function precompute_freqs_cis during model initialization. However, employing complex numbers is not standard practice in the realm of deep learning, particularly as lower-level tools such as Triton lack direct support for them. Fortunately, the operations can be easily reimplemented without relying on complex numbers, as we'll demonstrate.

Original llama code looks like that:

def precompute_freqs_cis(dim: int, end: int, theta: float = 10000.0):

# compute for each position the intensity of the embedding rotation

freqs = 1.0 / (theta ** (torch.arange(0, dim, 2)[: (dim // 2)].float() / dim))

t = torch.arange(end, device=freqs.device) # type: ignore

freqs = torch.outer(t, freqs).float() # type: ignore

freqs_cis = torch.polar(torch.ones_like(freqs), freqs) # operation on complex numbers

return freqs_cis

def reshape_for_broadcast(freqs_cis: torch.Tensor, x: torch.Tensor):

ndim = x.ndim

assert 0 <= 1 < ndim

assert freqs_cis.shape == (x.shape[1], x.shape[-1])

shape = [d if i == 1 or i == ndim - 1 else 1 for i, d in enumerate(x.shape)]

return freqs_cis.view(*shape)

def apply_rotary_emb(

xq: torch.Tensor,

xk: torch.Tensor,

freqs_cis: torch.Tensor,

) -> Tuple[torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor]:

# convert float to complex numbers by joining pairs of dimensions together

xq_ = torch.view_as_complex(xq.float().reshape(*xq.shape[:-1], -1, 2))

xk_ = torch.view_as_complex(xk.float().reshape(*xk.shape[:-1], -1, 2))

freqs_cis = reshape_for_broadcast(freqs_cis, xq_)

# apply rotation (the multplication) and convert back to float

xq_out = torch.view_as_real(xq_ * freqs_cis).flatten(3)

xk_out = torch.view_as_real(xk_ * freqs_cis).flatten(3)

return xq_out.type_as(xq), xk_out.type_as(xk)

Here's a brief look at the original Llama code:

- The function

precompute_freqs_ciscalculates a tensor, freqs, representing frequencies, which are subsequently combined with another tensor,t, to formulate a complex tensor freqs_cis using the polar function. - The

reshape_for_broadcastfunction adjusts the shape of thefreqs_cistensor to align with the dimensions of another tensor,x, ensuring compatibility for subsequent computations. - Lastly, the function

apply_rotary_embtakes the tensorsxqandxkand computes the output tensorsxq_outandxk_outusing the precomputedfreqs_cis.

These operations, originally executed using complex arithmetic, can be revamped by harnessing the innate simplicity of the computations involved. Also, phasing out precomputed factors can lead to a significant reduction in computation time.

When it comes to GPU computing, the rule of thumb is: computation is cheap, memory transfer is not. On recent GPU generations, memory transfer is over 100 times more costly per bit. Therefore, rewriting the operations in Triton should help us fuse operations and cut down on the overhead of saving and reloading data between operations.

Rewriting Without Complex Number Arithmetic

Our first move towards this goal is to reimplement rotary embeddings without PyTorch's complex number operations. This not only gives us a deep understanding of the operation, but also allows for a more seamless transition to the Triton implementation. We start with PyTorch due to its readability and ease of understanding.

Below we rewrote a part of the code without complex number operations:

def precompute_freqs_cis_pytorch(dim: int, end: int, theta: float = 10000.0):

assert dim % 2 == 0

# Generate a sequence of numbers from 0 to dim in steps of 2

sequence = torch.arange(0, dim, 2, dtype=torch.float32, device="cuda")

# Calculate frequency values based on the sequence and theta

freqs = 1.0 / (theta ** (sequence / dim))

# Create a tensor of numbers from 0 to end, it represents the position ids

t = torch.arange(end, device=freqs.device)

# Generate a table of frequency values

freqs = t[:, None] * freqs[None, :] # torch.outer(t, freqs).float()

# Calculate cosine and sine values for the frequencies

# These can be considered as the real and imaginary parts of complex numbers

freqs_cos = torch.cos(freqs)

freqs_sin = torch.sin(freqs)

# Return the cosine and sine values as two separate tensors

return freqs_cos, freqs_sin

def apply_rotary_emb_pytorch(x: torch.Tensor, freq_cos: torch.Tensor, freq_sin: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

# Split x and x into real and imaginary parts (by separating even and odd indices)

x_real = x[..., 0::2]

x_imag = x[..., 1::2]

# Reshape freq_cos and freq_sin for broadcasting

freq_cos = reshape_for_broadcast(freq_cos, x_real).to(torch.float32)

freq_sin = reshape_for_broadcast(freq_sin, x_imag).to(torch.float32)

# Perform the equivalent of complex number multiplication following the formula:

# (a + bi) * (c + di) = (ac - bd) + (ad + bc)i

x_out_real = x_real * freq_cos - x_imag * freq_sin

x_out_imag = x_real * freq_sin + x_imag * freq_cos

# Combine real and imaginary parts back into the original tensor

x_out = torch.stack((x_out_real, x_out_imag), dim=-1).flatten(-2)

return x_out.type_as(x)

Here's how we restructured a part of the code without complex number operations:

- The function precompute_freqs_cis_pytorch generates a range, computes frequency values based on this range, and then calculates cosine and sine values for these frequencies, which are returned as two separate tensors.

- The function apply_rotary_emb_pytorch splits the input tensors xq and xk into real and imaginary parts, reshapes freqs_cos and freqs_sin for broadcasting, performs calculations analogous to complex multiplication, and finally combines the real and imaginary parts back into the original tensor.

In practical terms, a complex number is simply a set of coordinates on a 2D plane. When we convert a float tensor to a complex tensor, we treat every pair of dimensions as a complex number. For this purpose, we utilize the indexing feature provided by PyTorch. Following the conversion, the tensor is reshaped.

The rotary embedding operations then apply specific transformations to each component of these complex numbers (the 2D

plane coordinates). The intensity of the transformation depends on the token's sequence position. This is achieved using

the standard formula for multiplying two complex numbers:

(a + bi) \* (c + di) = (ac - bd) + (ad + bc)i

Finally, the two tensors are merged, thus completing the process.

OpenAI Triton rewriting

In Triton, the operations look as follows:

@triton.jit

def rbe_triton(x_ptr, out_ptr,

M, K,

stride_x_batch, stride_x_m, stride_x_n,

stride_out_batch, stride_out_m, stride_out_n,

start_token_position,

THETA: tl.constexpr, BLOCK_SIZE_M: tl.constexpr, BLOCK_SIZE_K: tl.constexpr):

pid_batch = tl.program_id(axis=0)

pid = tl.program_id(axis=1)

pid_m = pid // tl.cdiv(K, BLOCK_SIZE_K)

pid_n = pid % tl.cdiv(K, BLOCK_SIZE_K)

offs_m = pid_m * BLOCK_SIZE_M + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_M)

offs_n = pid_n * BLOCK_SIZE_K + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_K // 2) * 2 # take only even numbers

x_ptrs = x_ptr + (pid_batch * stride_x_batch + stride_x_m * offs_m[:, None] + stride_x_n * offs_n[None, :])

x_real_mask = (offs_m[:, None] < M) & (offs_n[None, :] < K)

real = tl.load(x_ptrs, mask=x_real_mask, other=0.0)

x_imag_mask = (offs_m[:, None] < M) & (1 + offs_n[None, :] < K)

imag = tl.load(x_ptrs + 1, mask=x_imag_mask, other=0.0)

tl.debug_barrier()

start_block = start_token_position + pid_m * BLOCK_SIZE_M

cos, sin = get_freq_multi_tokens(offs_cn=offs_n, starting_idx=start_block, theta=THETA, NB_TOKENS=BLOCK_SIZE_M)

out_real = real * cos - imag * sin

out_imag = real * sin + imag * cos

tl.debug_barrier()

out_ptrs = out_ptr + (

pid_batch * stride_out_batch + stride_out_m * offs_m[:, None] + stride_out_n * offs_n[None, :])

out_real_mask = (offs_m[:, None] < M) & (offs_n[None, :] < K)

tl.store(out_ptrs, out_real, mask=out_real_mask)

out_imag_mask = (offs_m[:, None] < M) & (1 + offs_n[None, :] < K)

tl.store(out_ptrs + 1, out_imag, mask=out_imag_mask)

In Triton, we compose a program designed for concurrent execution - the raison d'être for leveraging GPUs in the first place. Triton operates on a lower level compared to PyTorch; while PyTorch abstracts most of global memory management (there are mechanisms like garbage collection, a memory pool, etc.), Triton allows for explicit control, enabling the user to directly manipulate the global memory addresses associated with specific sections of one or more tensors. Usually we work on a part of a tensor, called a "Tile" (this name is often used in gemm/matmul context). Yet, Triton also sits a notch above CUDA by automating certain aspects of memory management, such as transferring data between shared memory and registers, thus alleviating the complexity for the end user. As you may have noted, in the GPU world, many things are memory related.

To accomplish this, we simply load data from some specific GPU's global memory addresses, and do the same to store the data. Keep in mind that data is stored in global memory (the DDR of the GPU, which is slow and has high latency, typically in the range of hundreds of cycles) and we move it to the shared memory and registers (fast on-chip memory with latency in the tens of cycles) so we can manipulate them.

In the aforementioned program, we commence by determining the position of the start of the data block we will be operating on based on the program id (pid). Subsequently, we must determine which portion of the tensor we specifically require. For this purpose, we manipulate the addresses in a way where we load even and odd dimensions independently (into two different tensors named "real" and "imag"). This data transfer is crucial.

@triton.jit

def rbe_triton(x_ptr, out_ptr,

M, K,

stride_x_batch, stride_x_m, stride_x_n,

stride_out_batch, stride_out_m, stride_out_n,

start_token_position,

THETA: tl.constexpr, BLOCK_SIZE_M: tl.constexpr, BLOCK_SIZE_K: tl.constexpr):

pid_batch = tl.program_id(axis=0)

pid = tl.program_id(axis=1)

pid_m = pid // tl.cdiv(K, BLOCK_SIZE_K)

pid_n = pid % tl.cdiv(K, BLOCK_SIZE_K)

offs_m = pid_m * BLOCK_SIZE_M + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_M)

offs_n = pid_n * BLOCK_SIZE_K + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_K // 2) * 2 # take only even numbers

# ...

For this load operation, we generate a range from 0 to half the row's length, which we then multiply by 2 to obtain even addresses. To get odd ones, we simply add 1 to these even addresses. We add the tensor's storage beginning address to access the actual data.

# ...

x_ptrs = x_ptr + (pid_batch * stride_x_batch + stride_x_m * offs_m[:, None] + stride_x_n * offs_n[None, :])

x_real_mask = (offs_m[:, None] < M) & (offs_n[None, :] < K)

real = tl.load(x_ptrs, mask=x_real_mask, other=0.0)

x_imag_mask = (offs_m[:, None] < M) & (1 + offs_n[None, :] < K)

imag = tl.load(x_ptrs + 1, mask=x_imag_mask, other=0.0)

# ...

Following that, we compute the frequency values using the cos/sin functions and store the result. This is done in a manner reminiscent of Pytorch / numpy APIs.

When compared with the Pytorch implementation, our Triton kernel is 4.94 times faster! (from 0.027ms to 0.006ms, CUDA time measured on a 3090 RTX).

Unleashing Enhanced Efficiency: Simplified Fusions in RMSNorm Computation With Triton

The second operation we target for optimization is RMSNorm. This operation adjusts each input element by dividing it by the square root of the mean of all element squares, also known as the Root Mean Square (RMS).The goal of this operation is to normalize the data within the tensor to a standard scale and make the whole training more stable.

In PyTorch, six chained operations are needed to accomplish this:

def rms_norm_pytorch(x: torch.Tensor, rms_w: torch.Tensor, eps=1e-6) -> torch.Tensor:

x = x * torch.rsqrt(x.pow(2).mean(-1, keepdim=True) + eps)

return x * rms_w

``````

In contrast, Triton allows us to load the data once and conduct all necessary operations, which includes the

multiplication by the RMSNorm weights.

The Triton code would be:

```python

@triton.jit

def rmsnorm_triton(x_ptr, rms_w_ptr, output_ptr,

stride_x_batch, stride_x_m, stride_x_k,

stride_rms_w,

stride_out_batch, stride_out_m, stride_out_k,

N_SIZE: tl.constexpr, eps: tl.constexpr, BLOCK_N_SIZE: tl.constexpr):

pid_batch = tl.program_id(0)

pid_m = tl.program_id(1)

offs_m = pid_batch * stride_x_batch + pid_m * stride_x_m

block_N = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_N_SIZE)

var = tl.zeros((BLOCK_N_SIZE,), tl.float32)

# first loop over input tensor to compute the root mean of the square

for block_n_start_idx in range(0, N_SIZE, BLOCK_N_SIZE):

offs_n = block_n_start_idx + block_N

x_ptr_mask = offs_n < N_SIZE

# recompute address at each iteration

x = tl.load(x_ptr + offs_m + offs_n * stride_x_k, mask=x_ptr_mask, other=0.0)

var += tl.math.pow(x.to(tl.float32), 2)

# we keep this reduction operation outside the loop for perf reasons

var = tl.sum(var, axis=0) / N_SIZE

rstd = tl.math.rsqrt(var + eps)

# apply the normalization and multiply by RMS weights

for block_n_start_idx in range(0, N_SIZE, BLOCK_N_SIZE):

offs_n = block_n_start_idx + block_N

x_ptr_mask = offs_n < N_SIZE

rms_w = tl.load(rms_w_ptr + offs_n * stride_rms_w, mask=x_ptr_mask)

x = tl.load(x_ptr + offs_m + offs_n * stride_x_k, mask=x_ptr_mask, other=0.0).to(tl.float32)

x_hat = x * rstd

out = x_hat * rms_w

out_off = pid_batch * stride_out_batch + pid_m * stride_out_m + offs_n * stride_out_k

tl.store(output_ptr + out_off, out, mask=x_ptr_mask)

In this Triton version, we have two data passes:

- The first loop reads the data and calculates RMSNorm statistics.

- The second loop modifies the read data using the statistics calculated in the previous step.

An important point to bear in mind is that when two consecutive load operations are carried out on the same addresses, the second operation is likely to get the data from the GPU cache, meaning it doesn't cost double DDR loading to perform two passes within the same Triton program.

In Triton, certain specifics matter. For instance, the reduction operation (sum) is executed outside the loop due to its cost (this CUDA presentation: https://developer.download.nvidia.com/assets/cuda/files/reduction.pdf will give you a basic understanding of how complicated reductions are at warp level).

We also employ masks when loading and storing tensors. These masks are critical to avoid illegal memory access when dealing with fixed-size blocks that could potentially include addresses beyond the tensor boundary.

With this Triton version, we are 2.3 times faster than PyTorch in CUDA time! (from 0.021 ms to 0.009 ms)

Converging complex operations into a big fat kernel: RMSNorm, matrix multiplication, and rotary embeddings

In the third step, we take a holistic approach, targeting an array of operations: RMSNorm for data normalization, token projections (accomplished by matrix multiplication), and, lastly, rotary embeddings.

RMSNorm costlier task is data loading, executing in two distinct passes. Just after, during matrix multiplication from output of RMSNorm and model weight (to perform the projection), an iteration over the input tensor is performed. This situation presents an opportunity to compute the necessary statistics for RMSNorm. As the transformation entails dividing the input by a specific value, we can execute this operation _ post _ the tile matrix multiplication. Essentially, it means we can merge these two operations: executing matrix multiplication on a tensor prior to normalization and then normalizing its (tile) output.

Post-matrix multiplication, we can incorporate the output with the rotary embedding.

Given that all operations are being chained together, even if some of them necessitate writing to DDR, they will likely remain in the cache, significantly accelerating the process.

Here's the resulting OpenAI Triton code snippet:

@triton.jit

def rms_matmul_rbe(

x_ptr, w_ptr, rms_w_ptr, out_ptr,

M, N, K,

stride_x_batch, stride_x_m, stride_x_k,

stride_w_k, stride_w_n,

stride_rms_w,

stride_out_batch, stride_out_m, stride_out_n,

start_token_position,

RBE_EPILOGUE: tl.constexpr,

THETA: tl.constexpr,

EPS: tl.constexpr,

BLOCK_SIZE_M: tl.constexpr, BLOCK_SIZE_N: tl.constexpr, BLOCK_SIZE_K: tl.constexpr,

):

"""

Prologue: RMS

Epilogue: nothing or Rotary embeddings

c = ROBE((rms(a) * rms_w) @ b)

"""

pid_batch = tl.program_id(axis=0)

pid = tl.program_id(axis=1)

pid_m = pid // tl.cdiv(N, BLOCK_SIZE_N)

pid_n = pid % tl.cdiv(N, BLOCK_SIZE_N)

offs_m = (pid_m * BLOCK_SIZE_M + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_M)) % M

offs_n = (pid_n * BLOCK_SIZE_N + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_N)) % N

offs_k = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_K)

x_ptrs = x_ptr + (pid_batch * stride_x_batch + offs_m[:, None] * stride_x_m + offs_k[None, :] * stride_x_k)

w_ptrs = w_ptr + (offs_k[:, None] * stride_w_k + offs_n[None, :] * stride_w_n)

accumulator = tl.zeros((BLOCK_SIZE_M, BLOCK_SIZE_N), dtype=tl.float32)

rms_w_ptrs = rms_w_ptr + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_K)[None, :] * stride_rms_w

x_sum = tl.zeros((BLOCK_SIZE_M, BLOCK_SIZE_K), dtype=tl.float32)

# we do both RMSNorm stat computation, RMS weight multiplication...

# and matmul between input and linear weight (proj)

for _ in range(0, tl.cdiv(K, BLOCK_SIZE_K)):

x = tl.load(x_ptrs)

x_sum += tl.math.pow(x.to(tl.float32), 2) # RMSNorm stat computation

rms_w = tl.load(rms_w_ptrs)

x = x * rms_w # RMS weight multiplication

w = tl.load(w_ptrs)

accumulator += tl.dot(x, w) # matmul between input and linear weight (QKV projection)

x_ptrs += BLOCK_SIZE_K * stride_x_k # next input blocks by increasing the pointer

w_ptrs += BLOCK_SIZE_K * stride_w_k

rms_w_ptrs += BLOCK_SIZE_K * stride_rms_w

x_mean = tl.sum(x_sum, axis=1) / K + EPS

x_norm = tl.math.rsqrt(x_mean)

accumulator = accumulator * x_norm[:, None] # applies RMSNorm on the output of the matmul

offs_m = pid_m * BLOCK_SIZE_M + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_M)

offs_n = pid_n * BLOCK_SIZE_N + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_N)

out_ptrs = out_ptr + (pid_batch * stride_out_batch + offs_m[:, None]

* stride_out_m + offs_n[None, :] * stride_out_n)

out_mask = (offs_m[:, None] < M) & (offs_n[None, :] < N) # mask to avoid out of bound writes

if RBE_EPILOGUE: # if we want to apply rotary embeddings (for QK, not V)

tl.store(out_ptrs, accumulator, mask=out_mask)

tl.debug_barrier()

rbe_triton(out_ptr, out_ptr, M, N, stride_out_batch, stride_out_m, stride_out_n, stride_out_batch, stride_out_m,

stride_out_n, start_token_position, THETA,

BLOCK_SIZE_M, BLOCK_SIZE_N)

else:

tl.store(out_ptrs, accumulator, mask=out_mask)

Within this optimization process, the employment of rotary embedding is considered optional as it is only used for Q and K tensors, and not for the V tensor (RBE_EPILOGUE bool parameter).

The kernel's initial instructions focus on determining the precise position for starting the data reading process. The

loop then conducts three primary operations: projection (i.e., the matrix multiplication), multiplication with the

RMSNorm weight, and conveniently, the computation of statistics for RMSNorm, facilitated by the ongoing data read. The

implementation of RMSNorm is eventually accomplished through the operation:

accumulator = accumulator * a_norm[:, None]

After applying RMSNorm, the accumulator encapsulates the post-RMSNorm tile. This then proceeds to the 'epilogue', which involves the application of RBE. Here, it's crucial to note the synchronization barrier. When read/write operations occur simultaneously on a shared address, it's essential to ensure all threads within a single warp finish synchronously. If they don't, this may lead to intricate debugging issues related to concurrency.

However, it's worth noting an essential trade-off: the fusion of RMSNorm and matrix multiplication leads to more computation than strictly necessary. Specifically, for each tile (part of a tensor), the process recalculates the statistics of the whole input row and then normalizes the tile. This approach is primarily based on the fact that in the context of small batches (and likely not relevant for larger batches where global memory I/O and CPU overhead are efficiently managed and amortized), we are limited by memory bandwidth. As a result, this additional computation is deemed acceptable. Nevertheless, for larger batches, it's certainly a good idea to compare the performance profile between the fused and unfused RMSNorm operations.

The Triton kernel demonstrates a 1.52-fold performance improvement over the PyTorch code, reducing the CUDA execution time from 0.097 ms to 0.064 ms. The reason the speed boost isn't higher is largely due to the fact that the matrix multiplication performed for the projection isn't considerably faster in Triton than it is in PyTorch. This is primarily because the process of moving weights from the global memory to the on-chip memory is time-consuming, and this remains true regardless of the optimization strategy implemented. Nevertheless, a 1.5-fold increase in speed is a significant improvement worth noting.

Streamlining the Feed Forward Section of LLAMA: A Detailed Exploration

In LLAMA, the final section of the model is the feed-forward component, which in PyTorch is represented as follows:

def ff_pytorch(x: torch.Tensor, w1: torch.Tensor, w3: torch.Tensor, rms_w: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

x_norm = rms_norm_pytorch(x, rms_w, eps=1e-6)

a = torch.nn.functional.silu(torch.matmul(x_norm, w1.t()))

b = torch.matmul(x_norm, w3.t())

return a * b

In this function, the rms_norm_pytorch operation is identical to the one described in the first part of this article.

The following operations feature x_norm as an input twice, each instance being used in separate matrix

multiplications. The first matrix multiplication is succeeded by a silu operation, represented as follows:

input * torch.sigmoid(input)

This essentially breaks down to two straightforward element-wise operations. The entire process is completed with an elementary multiplication operation.

Observing that x_norm is employed at two separate points, we can optimize this by loading the data once and then

chaining the two matrix multiplications (in the same for loop). To further enhance this, we can merge RMSNorm into this

operation the same way we did before, thereby applying it only once as the output is reutilized. It may look like

something like that:

for _ in range(0, tl.cdiv(K, BLOCK_SIZE_K)):

a = tl.load(a_ptrs)

a += tl.load(res_ptrs)

# compute RMS stat

a_sum += tl.math.pow(a.to(tl.float32), 2)

rms_w = tl.load(rms_w_ptrs)

a = a * rms_w

b = tl.load(w1_ptrs)

acc1 += tl.dot(a, b) # matmul 1

c = tl.load(w3_ptrs)

acc2 += tl.dot(a, c) # matmul 2 chained in the same loop

# move the pointers, etc.

# …

# apply RMS statistics

# …

The silu operation, being made of two element-wise operations, can also be merged with the output of the first matrix multiplication, leading to an overall more streamlined operation.

At the end, our new kernel is 1.20 faster than Pytorch implementation (CUDA time, from 0.311 ms to 0.258 ms).

Understanding the Impact of Kernel Merging on CUDA and Wall Time Performance

CUDA time" refers to the execution time spent on the GPU for processing CUDA kernels. It reflects the time taken to execute CUDA commands and perform computations on the GPU itself, excluding the overheads of launching the kernels, transferring data between the CPU and GPU, and other operations.

On the other hand, "Wall time" (or "real time") accounts for the entire end-to-end execution time of the program, from start to finish. This includes not only the GPU computation time (CUDA time), but also the time taken for data transfers between the CPU and GPU, time taken to launch kernels, CPU-side computations, and any other operations related to program execution.

Kernel merging offers a notable computational advantage, let's say reducing CUDA time by 30% through optimization of the computation process. However, a second advantage lies in the reduction of kernel launch numbers and other possible overheads. These factors significantly contribute to the total wall time, particularly in situations where computations are relatively limited, such as in inference, and more so when the batch size is set to 1 like here.

That's why the improvement in wall time can be significantly larger than the improvement in CUDA time when merging kernels. By merging kernels, you essentially streamline the process, reducing the overheads related to kernel launching and data transfers, and therefore speed up the total program execution considerably.

FP8 for the fun

[this part has only been tried on llama 1, implementation for llama 2 will come later as we need to adapt Flash attention kernel]

In a significant move in 2022, Nvidia, Intel, and ARM collectively declared their endorsement for a unified FP8 format (read more here: https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/nvidia-arm-and-intel-publish-fp8-specification-for-standardization-as-an-interchange-format-for-ai/).

This data type introduces two distinct variants: E4M3 and E5M2, featuring a 4-bit exponent coupled with a 3-bit mantissa, and a 5-bit exponent partnered with a 2-bit mantissa, respectively. To clarify, the exponent determines the scale or range of the number, while the mantissa captures its significant figures. In the machine learning sphere, the E4M3 variant, known for its higher precision, is commonly associated with inference tasks, while E5M2, with its expansive range, is often preferred for training purposes. Notably, the 5-bit exponent aligns precisely with the FP16 format, implying that both formats can represent the same range of values. Consequently, transitioning from the latter to the former implies minimal effort. However, it's essential to consider that this replacement would come with a significant reduction in precision.

On Nvidia hardware, support of FP8 starts with Ada Lovelace / Hopper architectures (aka 4090, H100). H100 can run 2000 TFLOPS, the same number of operations per second as int8 and 2 times faster than FP16. As a comparison, A100 can run 312 TFLOPS.

Outside of speed, one of the advantages of FP8 is that it's almost a drop-in solution to reduce model size by 2. Unlike int8 quantization, you don't need to find the right scaler, etc.

A few months ago, OpenAI's Triton team and their Nvidia friends improved FP8 support in Triton for A100 and 3090 GPUs among others. What Triton does is that it executes operations of tensors encoded in FP8 on tensor cores in FP16. What is very surprising is that it runs close to peak FP16 performances, said otherwise, it has been implemented in a way where conversion cost is quite low. This is very unusual, as many have shared like here (https://twitter.com/tim_dettmers/status/1661380181607456768?s=61&t=cjtkVuHfEm4EoE-7aFHjAg).

Below we will see what it takes to support this new format.

First, we need to convert fp16 tensors to FP8 equivalent.

It can be done with such function:

def f16_to_f8(x: torch.Tensor, dtypes=tl.float8e5) -> torch.Tensor:

assert x.dtype in [torch.float16, torch.float32]

assert "cuda" in str(x.device), f"CUDA tensors only but got {x.device}"

@triton.jit

def kernel(Y, X, N, BLOCK_SIZE: tl.constexpr):

pid = tl.program_id(0)

offs = pid * BLOCK_SIZE + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE)

mask = offs < N

x = tl.load(X + offs, mask=mask)

tl.store(Y + offs, x, mask=mask)

ret = torch.empty_like(x, dtype=torch.int8)

grid = lambda META: (triton.cdiv(x.numel(), META['BLOCK_SIZE']),)

numel = x.untyped_storage().size() // x.element_size() # manage cases where tensor is not contiguous, like ::2

kernel[grid](triton.reinterpret(ret, dtypes), x, numel, BLOCK_SIZE=1024)

return ret

As you may notice, it's like we copy data from one place to another. Typing information is in the caller.

For PyTorch, the tensor is an int8, but we wrap it, and attach the information that inside the data is organized as an FP8.

Then in each kernel we do something like that to convert FP8 to FP16 (remaining of the kernel is identical than before having support for FP8):

tensor = tl.load(tensor_ptrs)

if USE_FP8:

# PyTorch has not yet a FP8 dtype, so we store it as an int8

# first we declare that tensor is indeed a FP8 and not an int8

tensor = tensor.to(tl.float8e5, bitcast=True)

# then we convert to FP16 as Ampere does not perform computation in FP8

# the magic thing is that the conversion costs close to nothing

tensor = tensor.to(tl.float16)

USE_FP8 is a constant expression (some info which is compiled) provided as an argument to the kernel.

To run end-to-end this model, we use a modified version of Flash Attention which supports FP8.

We measured perplexity and noticed a few percent degradation.

Disclaimer

Please note that this code represents a side project and has not been thoroughly optimized. The chosen tile sizes have been configured to function well with a 3090 RTX; however, for other GPUs, you may need to adjust these parameters. These settings have also been tailored for a batch size of one. If you intend to run the code on larger batch sizes, these parameters may not be suitable. It is advised to profile the code at each batch size you plan to use on the hardware you will run on prod, and hard code the best tile size for each of these scenarios.

For very large batches, it might be beneficial not to fuse matmul and RMSNorm as the computational intensity may increase, but profiling should ultimately guide this decision.

It has been observed that the fusion does not affect perplexity (as expected). However, the use of Flash Attention does have a minor impact on perplexity. In this project, Flash Attention is only utilized in the FP8 scenario. This could be attributable to a bug in our FA kernel implementation. We have implemented both the vanilla Triton and our own custom version specific to Llama, both lead to the same issue. Alternatively, it might not be a bug at all, but rather an instance of catastrophic cancelling at play. We didn't investigate this in depth as our primary aim was to test the FP8 format and its impact on speed.

Support of AMD GPUs in Triton brought some CPU overhead, for now it has not been fixed and those experiments has been ran on top of the commit 69a806c.